Partition 70 years on: When tribal warriors invaded Kashmir

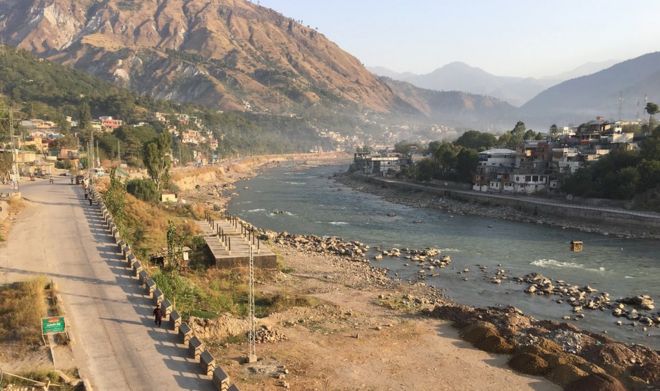

Towering some 550 metres (1,800 ft) above the Pakistani town of Garhi Habibullah to the west, and the Kashmiri city of Muzaffarabad to the east, Dub Gali looks serene on a cool October morning.

Some two dozen shops sit quietly on both sides of a security barrier that marks the border between Kashmir and the Pakistani province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

There is nothing to suggest that hordes of militant Pathan tribal warriors who invaded Kashmir exactly 70 years ago to start one of the world's most enduring territorial conflicts actually broke into the region through this very point.

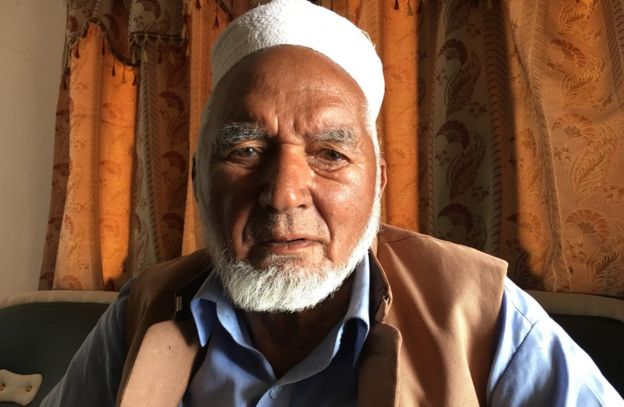

But a local villager, Mohammad Hasan Qureshi, 86, clearly remembers those stormy days.

"A week before the Pathans came, there were rumours that Kashmiri Sikhs [who had a significant population in this area] were planning to attack Muzaffarabad," he says.

"A couple of days later, we heard that Pathans were coming."

Such rumours were natural, coming as they did amid a series of upheavals that shook the princely state of Kashmir when the so-called 3 June Plan was announced.

Under the plan, British India, a Hindu-majority colony, was to be partitioned to create the Muslim state of Pakistan.

The fate of Kashmir, a princely state with a Muslim majority but a Hindu ruler, hung in the balance.

Muslims in the western districts of the state revolted against the ruling maharaja in June and there were anti-Muslim riots in southern Kashmir in September. There were also reports of a leaked Pakistani plan for raising a tribal column of 20,000 fighters to attack and annex Kashmir.

Mr Qureshi remembers the evening of 21 October, when he and some friends climbed a ridge to have a view of the western valley. They saw trucks carrying Pathans drive down the Batrasi hills into Garhi Habibullah.

"We stayed up all night, waiting. They came in the morning - just before daybreak. There were hundreds of them. Most of them carried axes and swords. Some had muskets, others just sticks. The Maharaja's guards at the barrier had vanished."

First clashes took place on their way down to Muzaffarabad, some 8km (5 miles) of steep descent.

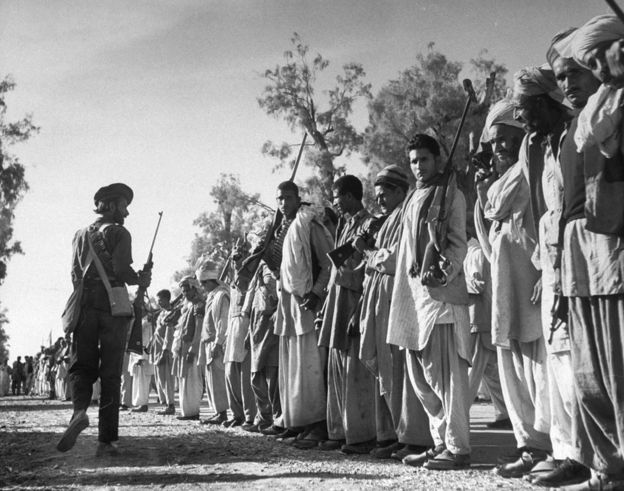

MARGARET BOURKE-WHITE/THE LIFE PICTURE COLLECTION/

MARGARET BOURKE-WHITE/THE LIFE PICTURE COLLECTION/

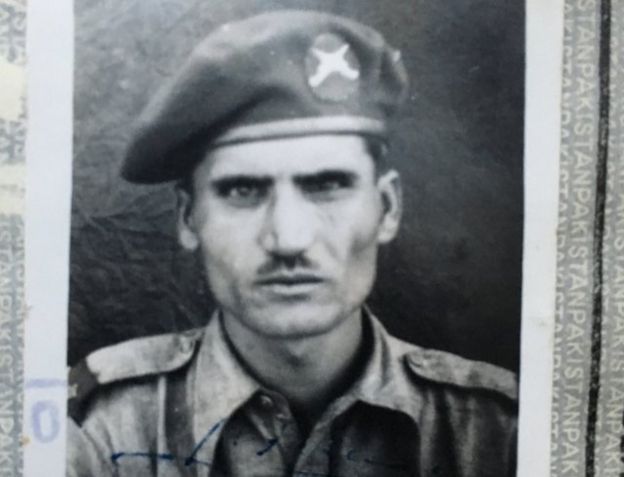

Gohar Rahman, a World War Two veteran from Battagram, 80km north-west of Garhi Habibullah, was in the column that crossed from Dub Gali.

"We knew the area so we led one group through this shorter route, on foot," he says.

"The bulk of the Frontier tribesmen - Wazir, Mahsud, Turi, Afridi, Mohmand, the Malakand Yusufzais - went via the longer but easier Lohar Gali route in lorries and trucks."

Around 2,000 tribesmen stormed Muzaffarabad that morning and easily scattered the Kashmir state army deployed there. Military historians estimate it was just 500-strong at the time and had also suffered defections by Muslim soldiers.

Partition of India in August 1947

- Perhaps the biggest movement of people in history, outside war and famine.

- Two newly independent states were created - India and Pakistan.

- About 12 million people became refugees. Between half a million and a million people were killed in religious violence.

- Tens of thousands of women were abducted.

Read more:

- Partition 70 years on: The turmoil, trauma - and legacy

- Special report: Partition - 70 years on

- How the Kashmir crisis began

Flushed with victory, the tribesmen got down to wanton looting and arson.

"They plundered the state armoury, set entire markets on fire and looted their goods," Mr Rahman says.

"They shot everyone who couldn't recite the kalima - the Arabic-language Muslim declaration of faith. Many non-Muslim women were enslaved, while many others jumped in the river to escape capture."

The streets were littered with signs of mayhem - broken buildings, broken shop furniture, the ashes of burnt goods and dead bodies, including those of tribal fighters, state soldiers and local men and women. There were also bodies floating in the river.

The raiders spent about three days in Muzaffarabad before sense prevailed and the leaders urged them to move on towards Srinagar, the state capital some 170km to the east.

From here, one column drove in trucks down the Jhelum river, breezing past Uri and reaching Baramulla where another round of looting and arson ensued.

Mr Rahman was part of the column that headed north on foot to Teetwal from where they turned east and went past Kupwara to arrive at the outskirts of Srinagar, a journey of well over 200km.

They did not face any resistance. The maharaja's army had scattered, and Hindus and Sikhs had fled the villages. They only met Muslims on the way.

"Muslim women would sometimes offer us food but the Pathans were reluctant to accept, thinking it may be poisoned. They would instead capture those people's goats and sheep, slaughter them and roast the meat on fire."

One night the fires attracted aircraft that dropped bombs, killing scores of them. "Bodies were strewn over a large area in a forest."

Unbeknown to them, the maharaja had by then signed an instrument of accession with India. Between 26 and 30 October, the Indians flew in enough troops to Srinagar to tilt the balance against tribal fighters.

The tribesmen still had numerical superiority but they were more adept at guerrilla war than infantry-style battles.

At that point, Pakistan's attempt to launch a formal attack on Srinagar in aid of the tribesmen was frustrated due to opposition from the British joint command of the as-yet-undivided militaries of India and Pakistan.

By November's end, the tribesmen had mostly pulled back to Uri, where the Jhelum gorge becomes narrower and easy to defend. Soon the winter snows arrived and put an end to the Indian advance towards Muzaffarabad.

It was here that the line that divides Kashmir between the Indian and Pakistani parts stabilised. Pakistani forces formally arrived on the scene in the spring of 1948 to reinforce this border.

- What is Kashmir like?

- A country divided: How partition affected me

- When teens from Kashmir and Delhi became pen pals

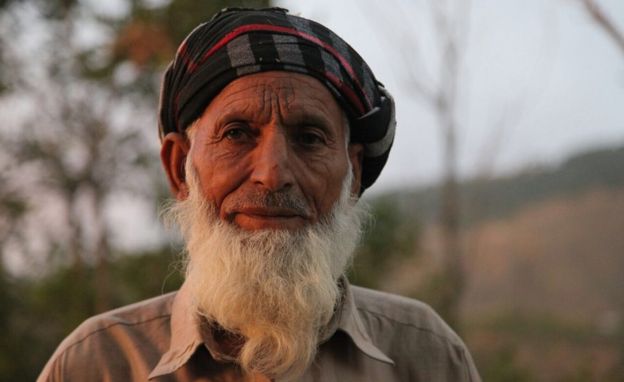

Hussain Gul, a resident of Shalozan village in the Kurram tribal region who was then a soldier of the paramilitary Kurram Militia, was part of that force.

"We were there to attack and recapture [the 2,800-metre] Pandu ridge which the Indians had occupied during autumn," he says.

"It was a good victory. We were able to occupy a considerable part of Kashmir but we still lost most of it. It made one feel sad, like when you lose a part of your house,"

His father, who went in with a band of friends to fight during the previous season, "came back defeated".

"They brought back war booty though; gold and some women," he chuckles.

In his mid-90s now, and with a fading memory, he is not sure what happened to the women. As for gold, "they were cheated out of it by Majoor", an ethnic Hazara businessman in Parachinar, the central town of Kurram.

Gohar Rahman returned to Garhi Habibullah when the first winter snows came. With him were many other tribesmen.

"They had returned with war booty," he says.

"Some had brought cattle, some horses. Most of them had brought arms, and many brought women. One Afridi tribesman walked back with two women in tow. They wept incessantly and just wouldn't stop. A local feudal lord took pity on them and forced the Afridi man to release them."

The invasion not only traumatised a previously well-settled and peaceful Kashmiri society, it also set a disastrous pattern for India-Pakistan relations.

- Is India losing Kashmir?

- The stolen childhoods of Kashmir in pencil and crayon

- The shopkeeper who lived through Kashmir's wars

Major-General Akbar Khan, an army officer who is widely believed to have played a pivotal role in starting the invasion, emerged as "the architect of (the) philosophy of armed insurrection by aiding non-state actors as state proxies", writes a military historian, Major (Retd) Agha Humayun Amin, in his book , The 1947-48 Kashmir War: The War of Lost Opportunities.

Pakistan repeated this strategy in Kashmir in 1965, during the Kashmir insurgency of 1988-2003, as well as in the Kargil War of 1999. It also used non-state actors in Afghanistan.

But instead of liberating Kashmir or taming Afghanistan, it has led to the weakening of political processes, and has militarised society not only in Kashmir and Afghanistan, but also in Pakistan.

A timeline of the tribal invasion

3 June 1947: The June Plan, also called the Mountbatten Plan, is approved in a meeting. It culminates in the Independence of India Act 1947 which partitions British India into independent states of India and Pakistan. The Act receives royal assent in July.

15 June: Agitation in the form of a No-Tax campaign starts in Poonch, an internal principality of Kashmir state.

15 August: Killings are reported from Bagh in Poonch principality when pro-Pakistan groups try to hoist a Pakistani flag to mark independence and clash with the state police.

12 September: Prime Minister of Pakistan Liaquat Ali Khan holds a meeting with military and civilian officials where a go-ahead is reportedly given to two plans: raise a tribal force to attack Kashmir from the north and arm the rebels in Poonch.

4 October: Rebels clash with state forces at a place called Thorar, and go on to besiege state forces in Poonch.

22 October: Tribal bands attack Muzaffarabad, then move eastwards to capture Baramulla. Some of the fighters reach the outskirts of Srinagar.

24 October: Sardar Ibrahim, a pro-Pakistan landlord from Poonch principality, announces the founding of the government of Azad (free) Jammu and Kashmir (AJK) at a place called Palandri, and appoints himself as its head.

26 October: The Maharaja of Kashmir, earlier inclined to stay independent due to the demographic composition of his state, accedes to India, presumably under duress.

27 October: Indian air and ground troops start landing at Srinagar, tilting the balance against tribal invaders and leading to the partition of Kashmir along the line that more or less exists today

Source: www.bbc.com By M Ilyas Khan

Comments

Post a Comment

Please be brief